WHO Antibiotic Categorization

-

Provides recommendations for 21 common infectious diseases

-

Classifies antibiotics into three groups based on the potential to induce and propagate resistance

-

Identifies antibiotics that are priorities for monitoring and surveillance of use

|

|

Bacteria

Bacteria are said to develop resistance when they are no longer inhibited or killed by a given antibiotic. Inappropriate use of antibiotics favors the emergence and spread of antibiotic resistance, amplifying natural ability of bacteria to resist |

|

Important

In order to keep antibiotics effective, we need to take them only when needed and strictly as directed by the prescriber / healthcare professional |

Furthermore, there is a need to select the right antibiotic for a given infection when they are needed. Those antibiotics that offer the best therapeutic advantage while minimizing the risk of resistance should be privileged |

|

The aim of the WHO AWaRe antibiotic categorization is to provide a tool to use antibiotics safely and effectively |

WHO

Antibiotic Categorization

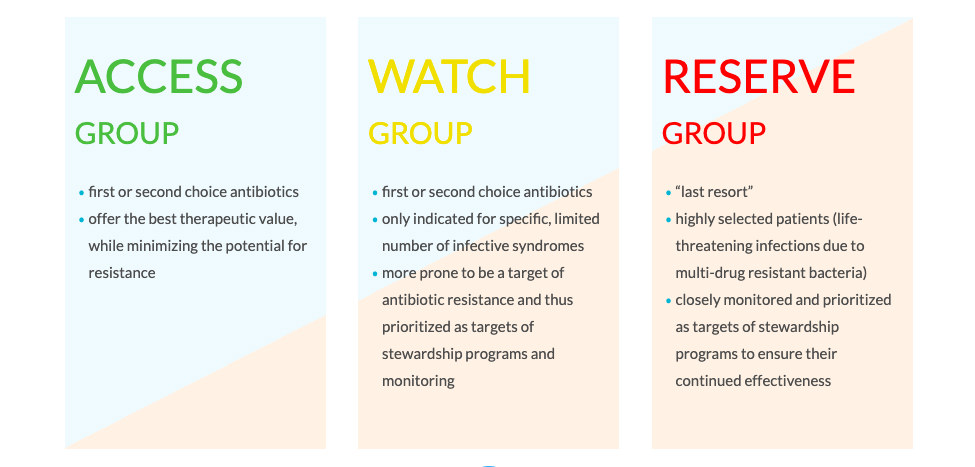

To address these issues, WHO developed a framework based on three different categories – Access, Watch and Reserve – which all together forms the AWaRe categorization of antibiotics:

All groups: sufficient supplies should exist worldwide

|

How were the antibiotic groups created and how can antibiotic selection be used to ensure the best health outcomes?

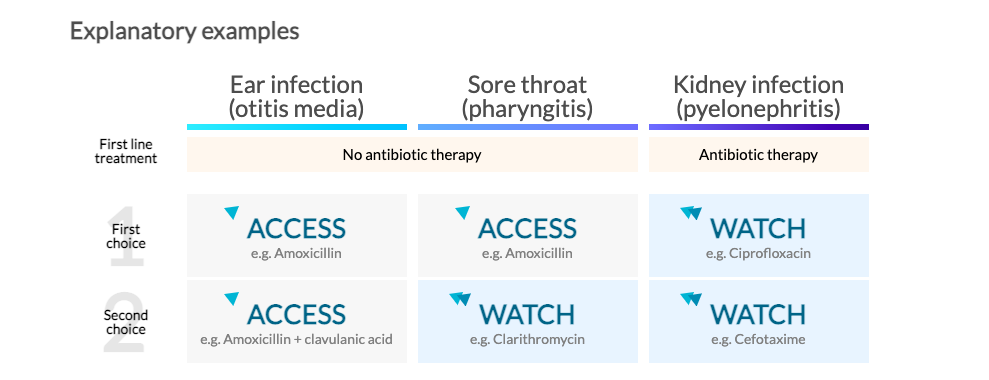

The AWaRe categorization illustrates which are the preferred antibiotic options for each syndrome, balancing benefits, harms and the

potential for resistance.

In 2017 WHO reviewed twenty one common infective syndromes, and selected the most appropriate first and second-choice antibiotic choices for each of the syndromes. The 2019 revision of the EML contains 37 antibiotics that are considered essential in treating 26 common and severe clinical infections, focusing on low-income and middle-income settings. The antibiotics were categorized following the AWaRe principles. However, to better understand how the antibiotics were divided into groups, three infective syndromes are used as explanatory examples below.

You may want to ask:

|

What does “watchful observation” mean? Nearly everybody has suffered from sore throat. From your own experience, you know that symptoms are often self-limited and can be cured without help of antibiotics. In fact, most cases of sore throat are caused by viruses, for which antibiotics do not work. For these reasons, the recommended first-line treatment for sore throat is watchful waiting. Symptoms usually improve within a few days without antibiotics. |

Why it is important to not use antibiotics as first-line treatment in conditions such as ear infections or sore throat? Not using antibiotics in such cases may help fight antibiotic resistance. It is increasingly recognized that antibiotics are non-renewable resources that should be used wisely, carefully weighing potential benefits against the risk of antibiotic resistance and other adverse events. When used parsimoniously, antibiotics will stay effective for use in serious cases and for vulnerable populations such as infants and the elderly. |

|

What is the difference between first and second choices? The first choice simply represents the best option in terms of effectiveness, harms and potential for resistance. In some cases, a second-choice antibiotic is also recommended. These antibiotics represent alternative options under some circumstances: they tend to be generally broader-spectrum antibiotics with higher resistance potential or less favorable risk–benefit ratios. Both first and second choices have specific indications (i.e. disease) for which they have been recommended. |

Why are some of the antibiotics in the table above marked with two triangles? These are antibiotics are in the WATCH group, which should be monitored by health authorities to prevent spread and further emergence of antibiotic resistance. Their use should be limited to infections where they provide clear benefits over antibiotics of the ACCESS group and should be avoided for other infections. It is important to outline, that the aim is not to avoid their use completely, but to limit their use to specific situations. By not overusing WATCH group antibiotics for conditions for which we have other options, we keep them effective for situations when they are needed. |

|

Is it possible that a WATCH (two triangles) antibiotic is first choice, followed by an ACCESS (one triangle)? Yes, this is true for example for meningitis, a very severe disease. This is due to the fact that antibiotics have different profiles in terms of effectiveness, safety, and resistance depending on the type of infection. It is therefore possible that the same WATCH group antibiotic is second choice for one infection, first choice for another infection and not recommended for a third infection. |

Are the WATCH (two triangles) antibiotics stronger? No. Antibiotics in the ACCESS group remain the “strongest”, most effective antibiotics for many infections. The classification in one of the AWaRe groups is based on their impact on antibiotic resistance and need for surveillance of use and is not based on differences in clinical effectiveness. |

|

What does it mean that the impact of antibiotics on different diseases is associated with different balance of benefits and harms? Consider the two examples shown above: ear infections and kidney infections. Most cases of ear infections in children are caused by viruses (for which antibiotics are not effective) and resolve spontaneously. Antibiotics provide a small reduction in pain beyond 24 hours in about 5 of 100 children treated. This also means that 95 of 100 of children treated with antibiotic will have no relevant benefit associated with antibiotic treatment. This potential modest benefit must be weighed against the potential harms related to antibiotic use, both for the individual patient (e.g. allergic reactions and other side effects like diarrhea that will afflict one in every five patients treated). Furthermore, antibiotics also kill “good” bystander organisms with unclear long-term consequences. Antibiotic resistance is another important side effect of antibiotic treatment, that can also affect other people through transmission. Kidney infections on the other hand require prompt medical attention. If not treated properly, a kidney infection can permanently damage your kidneys or the bacteria infection can spread to your bloodstream and put your life at risk. For this reason, it is important that a kidney infection is treated in a timely manner with effective antibiotics. For these severe infections the benefits associated with antibiotic treatment largely outweigh the side effects. However, an increasing number of people diagnosed with kidney infections have infections resistant to the standard class of antibiotic used in treatment – fluoroquinolones – severely limiting antibiotic treatment options. This resistance is partly driven by the use of fluoroquinolones for infections where other antibiotics would be preferable. |

|

WHO orchestrates collection of data on the spread of antimicrobial resistance (through the GLASS - Global Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System) and effectiveness of antibiotic stewardship programs. These findings will be presented here as soon as the data is available.

The Clock Is Ticking

The Clock Is Ticking

Antibiotic vs. Bacteria

Antibiotic vs. Bacteria